3

Pinocchio Icona Pop

Pinocchio Icona Pop

Pinocchio icona pop? Non certo solo per la significativa presenza dell’eroe di Carlo Collodi nelle opere di diversi artisti che hanno aderito a tale tendenza, ma anche per la smisurata e ininterrotta diffusione della sua immagine attraverso molteplici forme espressive. Pinocchio

ha continuato infatti a coinvolgerci nelle sue magiche - eppure così terribilmente realistiche - avventure: lo ritroviamo nelle illustrazioni delle centinaia di edizioni dedicate in tutte le lingue alla sua celebre storia; è stato immortalato da svariate tipologie di pupazzi e ancora continua a essere rappresentato nelle opere di artisti di ogni genere e provenienza; è inoltre comparso in carne e ossa (e legno) in diverse trascrizioni cinematografiche e fiction televisive o nei disegni animati del famoso lungometraggio di Walt Disney del 1940; nel 1952 fu consacrato dal parco ambientale di Collodi che, antesignano di molti di quelli recentemente intitolati in tutto il mondo a eroi del fumetto e della letteratura per l’infanzia, vide la collaborazione artistica e progettuale degli scultori Emilio Greco e Pietro Consagra e degli architetti Piero Porcinai, Marco Zanuso e Giovanni Michelucci; a Jesolo gli fu addirittura dedicata un’esposizione di sculture di sabbia, a conferma che la fama non determina necessariamente monumenti perenni.

Pinocchio ha comunque superato i famosi quindici minuti di celebrità che, all’interno dell’immaginario pop elaborato da Andy Warhol, dovrebbero essere riservati a ognuno di noi. La fama universale del burattino senza fili, titolo di un celebre album di Edoardo Bennato degli anni settanta, lo rende pertanto automaticamente un eroe dell’immaginario collettivo, al pari delle sue Marilyn e dei suoi Mao.

Non a caso la sua celebre immagine - quel naso lungo che è divenuto il segno distintivo e simbolico del personaggio - è stata rilanciata proprio dagli artisti pop, come l’americano Jim Dine o il piemontese Ugo Nespolo. Per Dine Pinocchio non ha rappresentato soltanto un soggetto del variegato universo della cultura pop: l’ibrido personaggio - vittima di sbalorditive mutazioni genetiche (come la crescita delle orecchie d’asino) - è stato per lui una vera e propria ossessione, incarnando il valore alchemico del fare arte. Nespolo invece ha interpretato la popolare storia del burattino di legno come modello iconografico del nostro immaginario collettivo, rielaborandola attraverso una rilettura ironica e festosa ispirata ai colori sgargianti delle opere di Depero e al suo universo artistico popolato da marionette e animati personaggi dalle forme meccaniche.

E proprio un ritratto di Pinocchio compare tra i tanti pupazzi prodotti dall’atelier del futurista trentino, quel pirotecnico laboratorio creativo passato alla storia come la Casa del Mago.

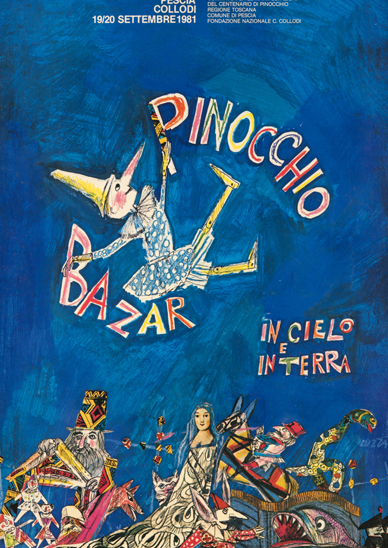

Come tutte le icone del nostro tempo, anche il nostro personaggio mostra quindi una multiforme adattabilità a ogni circostanza e ambientazione. E dunque il fiabesco e scherzoso burattino di legno di Lele Luzzati, memore delle suggestioni teatrali di Gozzi, può dialogare, come avviene in

questa mostra, con le cupe atmosfere del Pinocchio-Frankestein di Flavio Costantini, confermando una volta di più che se ognuno ha il suo Pinocchio, Pinocchio è davvero di tutti.

Matteo Fochessati

-

Pinocchio: A Pop Icon

Pinocchio, a pop icon? Not only because of the significant presence of Carlo Collodi’s hero in the works of various artists who have embraced this trend, but also due to the boundless and unceasing dissemination of his image across multiple expressive forms. Indeed, Pinocchio has continued to captivate us with his magical — and yet so terribly realistic — adventures. We find him in the illustrations of the hundreds of editions dedicated to his famous story, translated into every language; he has been immortalized in countless types of puppets and continues to be represented in the works of artists of all kinds and from every background. He has also appeared in the flesh (and in wood) in various cinematic and television adaptations, or in the animated drawings of Walt Disney’s famous 1940 feature film.

In 1952, he was consecrated by the environmental park of Collodi which — a forerunner of many similar parks later dedicated worldwide to comic book and children’s literature heroes — was realized with the artistic and design collaboration of sculptors Emilio Greco and Pietro Consagra, and architects Piero Porcinai, Marco Zanuso, and Giovanni Michelucci. In Jesolo, an entire sand sculpture exhibition was even dedicated to him — proof that fame does not necessarily require eternal monuments.

Pinocchio has, in any case, far exceeded the famous fifteen minutes of fame that, in Andy Warhol’s pop imagination, were supposed to be allotted to each of us. The universal fame of the “burattino senza fili” (the puppet without strings) — also the title of a celebrated album by Edoardo Bennato in the 1970s — automatically makes him a hero of the collective imagination, on par with Warhol’s Marilyns and Maos.

It is no coincidence that his famous image — that long nose which has become the distinctive and symbolic mark of the character — was revived precisely by pop artists such as the American Jim Dine and the Piedmontese Ugo Nespolo. For Dine, Pinocchio was not merely a subject within the varied universe of pop culture: this hybrid character — victim of astonishing genetic mutations (like the growth of donkey ears) — became for him a true obsession, embodying the alchemical value of making art itself.

Nespolo, on the other hand, interpreted the popular story of the wooden puppet as an iconographic model of our collective imagination, reworking it through an ironic and festive reinterpretation inspired by the vivid colors of Fortunato Depero’s works and his artistic world populated by marionettes and animated, mechanically shaped figures.

Indeed, a portrait of Pinocchio appears among the many puppets produced in the atelier of the Trentino futurist, that pyrotechnic creative workshop known to history as the Casa del Mago (“House of the Magician”).

Like all icons of our time, our character thus reveals a multifaceted adaptability to every circumstance and setting. Hence, the whimsical, fairy-tale wooden puppet of Lele Luzzati — echoing the theatrical enchantments of Gozzi — can, as happens in this exhibition, converse with the dark atmospheres of Flavio Costantini’s Pinocchio-Frankenstein, once again confirming that if everyone has their own Pinocchio, then Pinocchio truly belongs to everyone.

MATTEO FOCHESSATI

scopriindice

WebDesign & Content by Paroledavendere - Engineered by Pulsante

DATA WEB AGENCY

advent-c v2.0